Akira Toriyama

Akira Toriyama | |

|---|---|

鳥山明 | |

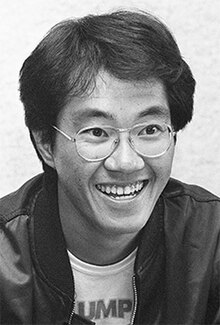

Toriyama in 1982 | |

| Born | April 5, 1955 |

| Died | March 1, 2024 (aged 68) Japan |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 1978–2024 |

| Employer | Shueisha |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Yoshimi Katō (m. 1982) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards |

|

| Signature | |

| |

Akira Toriyama (Japanese: 鳥山明, Hepburn: Toriyama Akira, April 5, 1955 – March 1, 2024[1]) was a Japanese manga artist and character designer. He first achieved mainstream recognition for creating the popular manga series Dr. Slump, before going on to create Dragon Ball (his most famous work) and acting as a character designer for several popular video games such as the Dragon Quest series, Chrono Trigger, and Blue Dragon. Toriyama came to be regarded as one of the most important authors in the history of manga with his works highly influential and popular, particularly Dragon Ball, which many manga artists cite as a source of inspiration.

He earned the 1981 Shogakukan Manga Award for best shōnen/shōjo manga with Dr. Slump, and it went on to sell over 35 million copies in Japan. It was adapted into a successful anime series, with a second anime created in 1997, 13 years after the manga ended.

His next series, Dragon Ball, would become one of the most popular and successful manga in the world. Having sold 260 million copies worldwide,[2][a][c] it is one of the best-selling manga series of all time and is considered to be one of the main reasons for the period when manga circulation was at its highest in the mid-1980s and mid-1990s. Overseas, Dragon Ball's anime adaptations have been more successful than the manga and are credited with boosting anime's popularity in the Western world. In 2019, Toriyama was decorated a Chevalier of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres for his contributions to the arts.

Early life

Akira Toriyama was born in the town of Kiyosu, Aichi Prefecture, Japan.[8][9] He had a younger sister.[10] Toriyama drew pictures since a young age, mainly of the animals and vehicles that he was fond of. He related being blown away after seeing One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), and said he was drawn deeper into the world of illustration by hoping to draw pictures that good.[11] He was shocked again in elementary school when he saw the manga collection of a classmate's older brother, and again when he saw a television set for the first time at a neighbor's house.[11] He cited Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy (1952–1968) as the original source for his interest in manga.[12] Toriyama recalled that when he was in elementary school all of his classmates drew imitating anime and manga, as a result of not having many forms of entertainment.[13] He believed that he began to advance above everyone else when he started drawing pictures of his friends.[13] Despite being engrossed with manga in elementary school, Toriyama said he took a break from it in middle school, probably because he became more interested in films and TV shows.[11] When asked if he had any formative experiences with tokusatsu entertainment, Toriyama said he enjoyed the Ultraman TV show and Gamera series of kaiju films.[14]

Toriyama said it was a "no-brainer" that he would attend a high school focused on creative design, but admitted he was more interested in having fun with friends.[11] Although he still did not read much manga, he would draw one himself every once in a while. Despite his parents' strong opposition, Toriyama was confident about going into the work force upon graduation instead of continuing his education.[11] He worked at an advertising agency in Nagoya designing posters for three years.[10] Although Toriyama said he adapted to the job quickly, he admitted that he was often late because he was not a "morning person" and got reprimanded for dressing casually. Resenting the routine, he became sick of the environment and quit.[11]

Career

Early work and Dr. Slump (1978–1983)

After quitting his job at the age of 23 and asking his mother for money, Toriyama entered the manga industry by submitting a work to an amateur contest in Kodansha's Weekly Shōnen Magazine, which he had randomly picked up in a coffee shop.[11][15] The timing did not line up for that contest, but another manga magazine, Weekly Shōnen Jump, accepted submissions for their Newcomer Award every month. Kazuhiko Torishima, who would become his editor, read and enjoyed Toriyama's manga, but it was not eligible to compete because it was a parody of Star Wars instead of an original work. Torishima sent the artist a telegram and encouraged him to keep drawing and sending him manga.[15][16] This resulted in Wonder Island, which became Toriyama's first published work when it appeared in Weekly Shōnen Jump in 1978. It finished last place in the readers survey.[11][15] Toriyama later said that he had planned to quit manga after getting paid, but because Wonder Island 2 (1978) was also a "flop", his stubbornness would not let him and he continued to draw failed stories for a year; claiming around 500 pages' worth, including the published Today's Highlight Island (1979).[11] He said he learned a lot during this year and even had some fun. When Torishima told him to draw a female lead character, Toriyama hesitantly created 1979's Tomato the Cutesy Gumshoe, which had some success. Feeling encouraged, he decided to draw another female lead and created Dr. Slump.[11]

Dr. Slump, which was serialized in Weekly Shōnen Jump from 1980 to 1984, was a huge success and made Toriyama a household name. It follows the adventures of a perverted professor and his small but super-strong robot Arale.[17] In 1981, Dr. Slump earned Toriyama the Shogakukan Manga Award for best shōnen or shōjo manga series of the year.[18] An anime adaptation began airing that same year, during the prime time Wednesday 19:00 slot on Fuji TV. Adaptations of Toriyama's work would occupy this time slot continuously for 18 years—through Dr. Slump's original run, Dragon Ball and its two sequels, and finally a rebooted Dr. Slump concluding in 1999. By 2008, the Dr. Slump manga had sold over 35 million copies in Japan.[19]

Although Dr. Slump was popular, Toriyama wanted to end the series within roughly six months of creating it, but publisher Shueisha would only allow him to do so if he agreed to start another serial for them shortly after.[20][21] So he worked with Torishima on several one-shots for Weekly Shōnen Jump and the monthly Fresh Jump.[22] In 1981, Toriyama was one of ten artists selected to create a 45-page work for Weekly Shōnen Jump's Reader's Choice contest. His manga Pola & Roid took first place.[11] Toriyama was selected to participate in the contest again in 1982 and submitted Mad Matic.[11] His one-shot Pink was published in the December issue of Fresh Jump.[23] Selected to participate in Weekly Shōnen Jump's Reader's Choice contest for a third time, Toriyama had the bad luck of drawing the first slot and had to work over New Year's on 1983's Chobit. Angry that it was unpopular, he decided to try again and created Chobit 2 (1983).[11]

An official Toriyama fan club, Akira Toriyama Hozonkai (鳥山明保存会, "Akira Toriyama Preservation Society"), was established in 1982. Its newsletters were called Bird Land Press and were sent to members until the club closed in 1987.[24] Toriyama founded Bird Studio in the early 1980s,[25] which is a play on his name; "tori" (鳥) meaning "bird". He began employing an assistant, mostly to work on backgrounds.

Dragon Ball and international success (1983–1997)

Torishima suggested that, as Toriyama enjoyed kung fu films, he should create a kung fu shōnen manga.[26] This led to the two-part Dragon Boy, published in the August and October 1983 issues of Fresh Jump.[23] It follows a boy, adept at martial arts, who escorts a princess on a journey back to her home country. Dragon Boy was well-received and evolved to become the serial Dragon Ball in 1984.[20][27] But before that, The Adventure of Tongpoo was published in Weekly Shōnen Jump's 52nd issue of 1983 and also contained elements that would be included in Dragon Ball.[23]

Serialized in Weekly Shōnen Jump from 1984 to 1995 and having sold 159.5 million tankōbon copies in Japan alone,[28] Dragon Ball is one of the best-selling manga series of all time.[29] It began as an adventure/gag manga but later turned into a martial arts fighting series, considered by many to be the "most influential shōnen manga".[17] Dragon Ball was one of the main reasons for the magazine's circulation hitting a record high of 6.53 million copies (1995).[30][31] At the series' end, Toriyama said that he asked everyone involved to let him end the manga, so he could "take some new steps in life".[32] During that near-11-year period, he produced 519 chapters that were collected into 42 volumes. Moreover, the success of the manga led to five anime adaptations, several animated films, numerous video games, and mega-merchandise. Aside from its popularity in Japan, Dragon Ball was successful internationally as well, including Asia, Europe, and the Americas, with 300–350 million copies of the manga sold worldwide.

While Toriyama was serializing Dragon Ball weekly, he continued to create the occasional one-shot manga. In 1986, Mr. Ho was published in the 49th issue of Weekly Shōnen Jump.[23] The following year saw publication of Young Master Ken'nosuke, which had a Japanese jidaigeki setting.[23] Toriyama published two Weekly Shōnen Jump one-shots in 1988; The Elder and Little Mamejiro.[23] Karamaru and the Perfect Day followed in issue #13 of 1989.[23]

Also during Dragon Ball's serialization, Torishima recruited him to work as character designer for the 1986 role-playing video game Dragon Quest. The artist admitted he was pulled into it without even knowing what an RPG was and that it made his already busy schedule even more hectic, but he was happy to have been a part after enjoying the finished game.[21] Toriyama continued to work on every installment in the Dragon Quest series until his death. He also served as the character designer for the Super Famicom RPG Chrono Trigger (1995) and for the fighting games Tobal No. 1 (1996) and Tobal 2 (1997) for the PlayStation.[33]

The September 23, 1988, festival film Kosuke & Rikimaru: The Dragon of Konpei Island marked the first time Toriyama made substantial contributions to an animation. He came up with the original story idea, co-wrote the screenplay with its director Toyoo Ashida, and designed the characters.[34] It was screened at the Jump Anime Carnival, which was held to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Weekly Shōnen Jump.[35]

Short stories and other projects (1996–2011)

A third anime adaptation based on Dragon Ball, entitled Dragon Ball GT, began airing in 1996, though this was not based on Toriyama's manga directly. He was involved in some overarching elements, including the name of the series and designs for the main cast.[36] Toriyama continued drawing manga in this period, predominantly one-shots and short (100–200-page) pieces, including Cowa! (1997–1998), Kajika (1998), and Sand Land (2000). On December 6, 2002, Toriyama made his only promotional appearance in the United States at the launch of Weekly Shōnen Jump's North American counterpart, Shonen Jump, in New York City.[37] Toriyama's Dragon Ball and Sand Land were published in the magazine in the first issue, which also included an in-depth interview with him.[38]

On March 27, 2005, CQ Motors began selling an electric car designed by Toriyama.[39] The one-person QVOLT is part of the company's Choro-Q series of small electric cars, with only 9 being produced. It cost 1,990,000 yen (about $19,000 US), has a top speed of 30 km/h (19 mph) and was available in five colors.[39] Toriyama stated that the car took over a year to design, "but due to my genius mini-model construction skills, I finally arrived at the end of what was a very emotional journey."[39]

He worked on a 2006 one-shot called Cross Epoch, in cooperation with One Piece creator Eiichiro Oda. The story is a short crossover that presents characters from both Dragon Ball and One Piece. Toriyama was the character designer and artist for the 2006 Mistwalker Xbox 360 exclusive RPG Blue Dragon, working with Hironobu Sakaguchi and Nobuo Uematsu, both of whom he had previously worked with on Chrono Trigger.[40] At the time, Toriyama felt the 2007 Blue Dragon anime might potentially be his final work in animation.[41]

In 2008, he collaborated with Masakazu Katsura, his good friend and creator of I"s and Zetman, for the Jump SQ one-shot Sachie-chan Good!!.[42][43] It was later published in North America in the free SJ Alpha Yearbook 2013, which was mailed out to annual subscribers of the digital manga magazine Shonen Jump Alpha in December 2012. The two worked together again in 2009, for the three-chapter one-shot Jiya in Weekly Young Jump.[44]

Toriyama was engaged by 20th Century Fox as a creative consultant on Dragonball Evolution, an American live-action film adaptation of Dragon Ball.[45] He was also credited as an executive producer on the 2009 film, which failed both critically and financially. Toriyama later stated in 2013 that he had felt the script did not "capture the world or the characteristics" of his series and was "bland" and not interesting, so he cautioned them and gave suggestions for changes. But the Hollywood producers did not heed his advice, "And just as I thought, the result was a movie I cannot call Dragon Ball."[46][47] Avex Trax commissioned Toriyama to draw a portrait of pop singer Ayumi Hamasaki, and it was printed on the CD of her 2009 single "Rule", which was used as the theme song to the film.[48]

Toriyama drew a 2009 manga titled Delicious Island's Mr. U for Anjō's Rural Society Project, a nonprofit environmental organization that teaches the importance of agriculture and nature to young children.[49] They originally asked him to do the illustrations for a pamphlet, but Toriyama liked the project and decided to expand it into a story. It is included in a booklet about environmental awareness that is distributed by the Anjō city government.[49] As part of Weekly Shōnen Jump's "Top of the Super Legend" project, a series of six one-shots by famed Jump artists, Toriyama created Kintoki for its November 15, 2010, issue.[50] He collaborated with Weekly Shōnen Jump to create a video to raise awareness and support for those affected by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011.[51]

Return to Dragon Ball (2012–2024)

In 2012, Dragon Ball Z: Battle of Gods was announced to be in development, with Toriyama involved in its creation. The film marked the series' first theatrical film in 17 years, and the first time Toriyama had been involved in one as early as the screenwriting stages.[52] The film opened on March 30, 2013. A special "dual ticket" that could be used to see both Battle of Gods and One Piece Film: Z was created with new art by both Toriyama and Eiichiro Oda.[53]

On March 27, 2013, the "Akira Toriyama: The World of Dragon Ball" exhibit opened at the Takashimaya department store in Nihonbashi, garnering 72,000 visitors in its first nineteen days.[54][55] The exhibit was separated into seven areas. The first provided a look at the series' history, the second showed the 400-plus characters from the series, the third displayed Toriyama's manga manuscripts from memorable scenes, the fourth showed special color illustrations, the fifth displayed rare Dragon Ball-related materials, the sixth included design sketches and animation cels from the anime, and the seventh screened Dragon Ball-related videos.[54] It was there until April 15, when it moved to Osaka from April 17 to 23, and ended in Toriyama's native Nagoya from July 27 to September 1.[54]

To celebrate the 45th anniversary of Weekly Shōnen Jump, Toriyama launched a new manga series in its July 13, 2013, issue titled Jaco the Galactic Patrolman.[56] Viz Media began serializing it in English in their digital Weekly Shonen Jump magazine, beginning just two days later.[57] The final chapter reveals that the story is set before the events of Dragon Ball and features some of its characters. It would become the final manga that Toriyama wrote and illustrated himself.

The follow-up film to Battle of Gods, Resurrection 'F', released on April 18, 2015, features even more contributions from Toriyama, who personally wrote its original script.[58] Toriyama provided the basic story outline and some character designs for Dragon Ball Super, which began serialization in V Jump in June 2015 with an anime counterpart following in July. Although the anime ended in 2018, he continued to provide story ideas for the manga while Toyotarou illustrated it.[59] Dragon Ball Super: Broly, released in theaters on December 14, 2018, and Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero, released on June 11, 2022, continued Toriyama's deep involvement with the films.[60][61]

In January 2024, a logo Toriyama designed to celebrate the 20th anniversary of his hometown of Kiyosu was unveiled.[62] Toriyama created a new story arc for the 2024 original net animation adaptation of his manga Sand Land.[63] He also created the story and character designs for the upcoming Dragon Ball Daima anime series.[64]

Personal life

Toriyama married Yoshimi Katō (加藤由美) on May 2, 1982.[65][66] She is a former manga artist from Nagoya under the pen name "Nachi Mikami" (みかみなち),[67] and occasionally helped Toriyama and his assistant on Dr. Slump when they were short on time.[68] They had two children: a son named Sasuke (佐助) born on March 23, 1987,[69] and a daughter named Kikka born in October 1990.[70][71] Toriyama lived in his home studio in Kiyosu.[25][72] He was a well-known recluse, who avoided appearing in public or media.[73][74][75] In an extension to his shyness, Toriyama had used an avatar called "Robotoriyama" since December 1980 to represent himself in manga and interviews.[76]

Toriyama had a love of cars and motorcycles, something he inherited from his father who used to race motorbikes and operated an auto repair business for a brief time, although he did not understand the mechanics himself.[77] The author was an animal lover, having kept many different species of birds, dogs, cats, fish, lizards, and bugs as pets since childhood.[77] Some were used as models for characters he created such as Karin and Beerus. Toriyama had a lifelong passion for plastic models,[77] and designed several for the Fine Molds brand. He also collected autographs of famous manga artists, having over 30 including Yudetamago and Hisashi Eguchi, a hobby he gave to the character Peasuke Soramame.[10][78]

Death

On March 1, 2024, Toriyama died of an acute subdural hematoma, at the age of 68. A funeral was held privately with only his family in attendance.[79][80] His death was announced by his production company Bird Studio one week later on March 8.[81] According to sources close to Toriyama, he had planned to undergo surgery for a brain tumor in February 2024.[82] The news of his death caused an outpouring of grief among admirers of his works, who took to social media to express their condolences and celebrate his legacy.[83][84] On Twitter, the trending topics of Akira Toriyama and Dragon Ball surpassed United States President Joe Biden's State of the Union address, which was held at the same time the news of Toriyama's death was announced.[85] Tributes to the artist were given by One Piece creator Eiichiro Oda, Naruto creator Masashi Kishimoto, Bleach creator Tite Kubo, My Hero Academia creator Kōhei Horikoshi, Yu Yu Hakusho and Hunter × Hunter creator Yoshihiro Togashi, Video Girl Ai creator Masakazu Katsura, and video game designer Yuji Horii, who worked with Toriyama on Dragon Quest and Chrono Trigger.[86][87] In Tokyo, fans publicly mourned while visiting a life-sized statue of Dragon Ball protagonist Goku located outside the headquarters of toy manufacturer Bandai.[88][89] Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshimasa Hayashi credited Toriyama and his work with playing an "extremely important role in demonstrating Japan's soft power" around the world.[90]

International response

French President Emmanuel Macron shared a photo of an autographed illustration Toriyama gave him as a gift and paid tribute to him and his fans on social media.[91] French Prime Minister Gabriel Attal also paid tribute and stated not even "the [Dragon Balls] and Shenron" could revive him.[92] The foreign ministries of China and El Salvador issued statements of condolences over Toriyama's death.[93][94] Justin Chatwin, who portrayed Goku in the live-action film Dragonball Evolution, apologized for the quality of the film by posting on his Instagram story, "sorry we messed up that adaptation so badly".[95] Several Mexican voice actors who dubbed Dragon Ball characters in Spanish for Latin America also lamented Toriyama's death via social media.[96] A large gathering was held at the Plaza de la Constitución in Mexico City, where hundreds of fans did the Genki-dama hand motion (arms up, palm facing the zenith, pooling energy together) to honor the artist.[97] During the 18th Seiyu Awards on March 9, a moment of silence was held for Toriyama and voice actress Tarako, who died on March 4, in recognition of their contributions to the anime industry.[98] On March 10, in Argentina, thousands of fans gathered at the Obelisco monument to remember Toriyama.[99] In Lima, Peru, over 40 artists led by "Peko" painted a mural tribute to Toriyama, which showcases characters from Dragon Ball as well as Toriyama himself, spanning six meters high and over 110 meters long.[100][101]

Style

Toriyama admired Osamu Tezuka's Astro Boy and was impressed by Walt Disney's One Hundred and One Dalmatians, which he remembered for its high-quality animation.[16][102] He was a fan of Hong Kong martial arts films, especially Bruce Lee films such as Enter the Dragon (1973) and Jackie Chan films such as Drunken Master (1978), which went on to have a large influence on his later work.[103][104][105] He also cited the science fiction films Alien (1979) and Galaxy Quest (1999) as influences.[106] Toriyama stated he was influenced by animator Toyoo Ashida and the anime television series adaptation of his own Dragon Ball, from which he learned that separating colors instead of blending them makes the art cleaner and coloring illustrations easier.[102]

It was Toriyama's sound effects in Mysterious Rain Jack that caught the eye of Kazuhiko Torishima, who explained that usually they are written in katakana, but Toriyama used the Roman alphabet, which he found refreshing.[107] Torishima has stated that Toriyama aimed to be a gag manga artist because the competitions that he submitted to early on required entries in the gag category to only be 15 pages long, compared to story manga entries which had to be 31.[15] In his opinion, Toriyama excelled in black and white, utilizing black areas as a result of not having had the money to buy screentone when he started drawing manga.[107] He also described Toriyama as a master of convenience and "sloppy, but in a good way." For instance, in Dragon Ball, destroying scenery in the environment and giving Super Saiyans blond hair were done in order to have less work in drawing and inking. Torishima claimed that Toriyama drew what he found interesting and was not mindful of what his readers thought,[108] nor did he get much inspiration from other comics, as he chose not to re-read previous works or read manga made by other artists, a practice that Torishima supported.[109] Furthermore, the book A History of Modern Manga (2023) describes Toriyama as "a perfectionist at heart" who "didn't hesitate to redraw entire panels under the worried eye of his editor at Jump".[110]

Dr. Slump is mainly a comedy series, filled with puns, toilet humor, and sexual innuendos. But it also contained many science fiction elements: aliens, anthropomorphic characters, time travel, and parodies of works such as Godzilla, Star Wars, and Star Trek.[17] Toriyama also included many real-life people in the series, such as his assistants, wife, and colleagues (such as Masakazu Katsura), but most notably his editor Kazuhiko Torishima as the series' main antagonist, Dr. Mashirito.[17][111] A running gag in Dr. Slump that utilizes feces has been reported as an inspiration for the Pile of Poo emoji.[112][113]

When Dragon Ball began, it was loosely based on the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West,[27][114] with Goku being Sun Wukong and Bulma as Tang Sanzang. It was also inspired by Hong Kong martial arts films,[115] particularly those of Jackie Chan,[116] and was set in a fictional world based on Asia, taking inspiration from several Asian cultures including Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Central Asian, Arabic, and Indonesian cultures.[17][117] Toriyama continued to use his characteristic comedic style in the beginning, but over the course of serialization this slowly changed, with him turning the series into a "nearly-pure fighting manga" later on.[17] He did not plan out in advance what would happen in the series, instead choosing to draw as he went. This, coupled with him simply forgetting things he had already drawn, caused him to find himself in situations that he had to write himself out of.[17]

Toriyama was commissioned to illustrate the characters and monsters for the first Dragon Quest video game (1986) in order to separate it from other role-playing games of the time.[118] He worked on every installment in the series until he passed away. For each game Yuji Horii first sends rough sketches of the characters with their background information to Toriyama, who then re-draws them. Lastly, Horii approves the finished work.[119][120] Toriyama explained in 1995 that for video games, because the sprites are so small, as long as they have a distinguishing feature so people can tell which character it is, he can make complex designs without concern of having to reproduce it like he usually would in manga.[121] Besides the character and monster designs, Toriyama also does the games' packaging art and, for Dragon Quest VIII, the boats and ships.[120] In 2016, Toriyama revealed that because of the series' established time period and setting, his artistic options are limited, which makes every iteration harder to design for than the last.[74] The series' Slime character, which has become a mascot for the franchise, is considered to be one of the most recognizable figures in gaming.[122]

Manga critic Jason Thompson declared Toriyama's art influential, saying that his "extremely personal and recognizable style" was a reason for Dragon Ball's popularity.[17] He points out that the popular shōnen manga of the late 1980s and early 1990s had "manly" heroes, such as City Hunter and Fist of the North Star, whereas Dragon Ball starred the cartoonish and small Goku, thus starting a trend that Thompson says continues to this day.[17] Toriyama himself said he went against the normal convention that the strongest characters should be the largest in terms of physical size, designing many of the series' most powerful characters with small statures.[123] Thompson concluded his analysis by saying that only Akira Toriyama drew like this at the time and that Dragon Ball is "an action manga drawn by a gag manga artist."[17] James S. Yadao, author of The Rough Guide to Manga, points out that an art shift does occur in the series, as the characters gradually "lose the rounded, innocent look that [Toriyama] established in Dr. Slump and gain sharper angles that leap off the page with their energy and intensity."[124]

Legacy and accolades

The role of my manga is to be a work of entertainment through and through. I dare say I don't care even if [my works] have left nothing behind, as long as they have entertained their readers.

—Akira Toriyama, 2013[125]

Patrick St. Michel of The Japan Times compared Toriyama to animator Walt Disney and Marvel Comics creator Stan Lee, "All three of these individuals, Toriyama included, had a personal artistic style that has become the shorthand for their respective media."[126] Speaking of Dragon Ball, David Brothers of ComicsAlliance wrote that: "Like Osamu Tezuka and Jack Kirby before him, Toriyama created a story with his own two hands that seeped deep into the hearts of his readers, creating a love for both the cast and the medium at the same time."[127] Thompson stated in 2011 that "Dragon Ball is by far the most influential shonen manga of the last 30 years, and today, almost every Shōnen Jump artist lists it as one of their favorites and lifts from it in various ways."[17] Patrick W. Galbraith, an associate professor at the School of International Communication at Senshu University, similarly said, "One can sense the DNA of Toriyama's work in all subsequent shōnen releases."[126]

In a rare 2013 interview, commenting on Dragon Ball's global success, Toriyama admitted, "Frankly, I don't quite understand why it happened. While the manga was being serialized, the only thing I wanted as I kept drawing was to make Japanese boys happy."[125] He had previously stated in 2010, "The truth is, I didn't like being a manga artist very much. It wasn't until relatively recently that I realized it's a wonderful job."[106] Many artists have named Toriyama and Dragon Ball as influences, including One Piece author Eiichiro Oda,[128] Naruto creator Masashi Kishimoto,[129] Fairy Tail and Rave author Hiro Mashima,[130] Boruto: Naruto Next Generations illustrator Mikio Ikemoto,[131] Venus Versus Virus author Atsushi Suzumi,[132] Bleach creator Tite Kubo, Black Cat author Kentaro Yabuki, and Mr. Fullswing author Shinya Suzuki.[133] German comic book artist Hans Steinbach was strongly influenced by Toriyama,[134] and Thai cartoonist Wisut Ponnimit cited Toriyama as one of his favorite cartoonists.[135] St. Michel wrote that the impact Toriyama and Dragon Ball had extends beyond inspiring newer artists, "he influenced the style of anime as a whole and revealed new economic potential, as the comic series mutated into an anime, video games and infinite merchandise."[126] Ian Jones-Quartey, a producer of the American animated series Steven Universe, is a fan of both Dragon Ball and Dr. Slump, and uses Toriyama's vehicle designs as reference for his own. He also stated that "We're all big Toriyama fans on [Steven Universe], which kind of shows a bit."[136] French director Pierre Perifel cited Toriyama and Dragon Ball as influences on his DreamWorks Animation film The Bad Guys.[137]

In 2008, Oricon conducted a poll of people's favorite manga artists, with Toriyama coming in second, behind only Nana author Ai Yazawa. He was number one among male respondents and among those over 30 years of age.[138] They held a poll on the Mangaka that Changed the History of Manga in 2010, mangaka being the Japanese word for a manga artist. Toriyama came in second, after only Osamu Tezuka, due to his works being highly influential and popular worldwide.[139] Toriyama won the Special 40th Anniversary Festival Award at the 2013 Angoulême International Comics Festival, honoring his years in cartooning.[140][141] He actually received the most votes for the festival's Grand Prix de la ville d'Angoulême award that year, though the selection committee chose Willem as the recipient.[142] In a 2014 NTT Docomo poll for the manga artist that best represents Japan, Toriyama came in third place.[143] That same year, entomologist Enio B. Cano named a new species of beetle, Ogyges toriyamai, after Toriyama, and another, Ogyges mutenroshii, after the Dragon Ball character Muten Roshi.[144] Toriyama was decorated a Chevalier or "Knight" of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French government on May 30, 2019, for his contributions to the arts.[73][145] He was also a 2019 nominee for entry into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame.[146] Toriyama was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2024 Tokyo Anime Awards Festival.[147] Due to his video game design work, IGN named Toriyama number 74 on their list of the Top 100 Game Creators of All Time.[33]

Works

Besides Dr. Slump (1980–1984) and Dragon Ball (1984–1995), Toriyama predominantly drew one-shot manga and short (100–200-page) pieces, including Pink (1982), Go! Go! Ackman (1993–1994), Cowa! (1997–1998), Kajika (1998), Sand Land (2000) and Jaco the Galactic Patrolman (2013). Many of his one-shots were collected in his three-volume anthology series, Akira Toriyama's Manga Theater (1983–1997). He also collaborated with other manga artists, such as Katsura and Oda,[148][149] to produce one-shots and crossover shorts.

Toriyama also created many character designs for various video games such as the Dragon Quest series (1986–2023), Chrono Trigger (1995), Blue Dragon (2006), and some Dragon Ball video games. He also designed several characters and mascots for various manga magazines property of Shueisha, his career-long employer and Japan's largest publishing company.[150][151][152]

Besides manga-related works, Toriyama also created various illustrations, album and book covers, model kits, mascots and logos.[153][154][155] For example, he sketched several versions of the Dragon Ball Z logo, which Toei Animation then refined into a definitive design.[156]

Explanatory notes

- ^ Other sources estimate the total Dragon Ball tankōbon sales worldwide to be 260 or 300 million copies.[3][4][5][6][7] See Dragon Ball (manga) § Reception for worldwide sales breakdown.

- ^ See Weekly Shōnen Jump § Manga series

- ^ In addition to tankōbon sales, Dragon Ball had a total estimated circulation of approximately 2.96 billion copies in Weekly Shōnen Jump magazine.[b]

References

- ^ Yoon, John; Notoya, Kiuko. "Akira Toriyama, Creator of 'Dragon Ball,' Dies at 68". The New York Times. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero Global Theatrical Release Dates". Toei Animation. June 15, 2022. Archived from the original on December 12, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ Johnson, G. Allen (January 16, 2019). "'Dragon Ball Super: Broly,' 20th film of anime empire, opens in Bay Area". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- ^ Booker, M. Keith (2014). Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. p. xxxix. ISBN 9780313397516. Archived from the original on February 10, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ 『ドラゴンボール超』劇場版最新作、2022年に公開決定. Toei Animation (in Japanese). May 9, 2021. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ ドラゴンボール超Dragon スーパーヒーロー:"930倍"超巨大2.4メートルの超ムビチケ好調 3日間で受注200件 想定以上の売れ行き. Mantan Web (in Japanese). March 7, 2022. Archived from the original on April 21, 2022. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "Top Manga Properties in 2008 - Rankings and Circulation Data". Comipress. December 31, 2008. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ 鳥山明が急性硬膜下血腫で死去、68歳. Natalie (in Japanese). March 8, 2024. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Yoon, John; Notoya, Kiuko (March 8, 2024). "Akira Toriyama, Creator of 'Dragon Ball,' Dies at 68". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c Toriyama, Akira (2009). Dr. Slump, Volume 11. Viz Media. pp. 48, 64, 80, 110. ISBN 978-1-4215-0635-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Toriyama, Akira (2021). Akira Toriyama's Manga Theater. Viz Media. pp. 22, 38, 99, 145, 191, 228, 280, 302, 348, 374. ISBN 978-1-9747-2348-5.

- ^ "Mangaka Who's Who - Akira Toriyama". Pafu. Zassōsha. September 1980.

- ^ a b DRAGON BALL 大全集 6: MOVIES & TV SPECIALS (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. pp. 212–216. ISBN 4-08-782756-9.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama Interview". Monthly Starlog. No. 11. Tsurumoto Room. 1980.

- ^ a b c d Konno, Daiichi (October 21, 2018). "『ジャンプ』伝説の編集長は『ドラゴンボール』をいかにして生み出したのか". ITmedia (in Japanese). Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b "none". Shonen Jump. No. 1. Viz Media. November 26, 2002.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Thompson, Jason (March 10, 2011). "Jason Thompson's House of 1000 Manga – Dragon Ball". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ 小学館漫画賞: 歴代受賞者 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ^ "Top Manga Properties in 2008 – Rankings and Circulation Data". Comipress. December 31, 2008. Archived from the original on June 30, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2013.

- ^ a b "Kazuhiko Torishima On Shaping The Success Of 'Dragon Ball' And The Origins Of 'Dragon Quest'". Forbes. October 15, 2016. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b Dragon Ball 超全集 4: 超事典 [Chōzenshū 4: Super Encyclopedia] (in Japanese). Shueisha. 2013. pp. 346–349. ISBN 978-4-08-782499-5.

- ^ "Shenlong Times 2". Dragon Ball 大全集 2: Story Guide (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. ISBN 4-08-782752-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g "鳥山明 THE WORLD アニメスペシャル". Weekly Shōnen Jump (in Japanese). Shueisha. October 10, 1990. pp. 72, 74, 75, 82–86.

- ^ [鳥山明ほぼ全仕事] 平日更新24時間限定公開! 2019/05/28. Dragon Ball Official Site (in Japanese). Shueisha. May 28, 2019. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved May 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Ashcraft, Brian (July 23, 2014). "Dragon Ball Is Made in a Very Orange Building". Kotaku. Archived from the original on August 24, 2016. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ Dragon Ball 大全集 2: Story Guide [Dragon Ball Complete Works 2: Story Guide] (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. pp. 261–265. ISBN 4-08-782752-6.

- ^ a b Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (September 1, 2001). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (1st ed.). Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press. pp. 101–102. ISBN 1-880656-64-7. OCLC 47255331.

- ^ "Shueisha Media Guide 2014: Boy's & Men's Comic Magazines" (PDF) (in Japanese). Shueisha. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2015. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ^ "Top 10 Shonen Jump Manga by All-Time Volume Sales". Anime News Network. October 23, 2012. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ Ibaraki, Masahiko (March 31, 2008). "The Reminiscence of My 25 Years with Shonen Jump". Translated by Ohara, T. ComiPress. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ "The Rise and Fall of Weekly Shonen Jump: A Look at the Circulation of Weekly Jump". ComiPress. May 8, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Toriyama, Akira (1995). Dragon Ball, Volume 42. Shueisha. ISBN 978-4-08-851090-3.

- ^ a b "74. Akira Toriyama". IGN. Archived from the original on June 16, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "小助さま 力丸さま コンペイ島の竜". J.C.Staff (in Japanese). Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Taniguchi, Riuichi (March 11, 2024). "漫画・アニメ・ゲームすべてに新たな扉を開いた鳥山明、その大きすぎる功績を振り返る". IGN Japan (in Japanese). Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Dragon Ball GT Dragon Box: Dragon Book (in Japanese). Pony Canyon. 2005. p. 1.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama To Appear at Shonen Jump Launch Party". Anime News Network. December 2, 2002. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ "Shonen Jump No. 1 Contents". Anime News Network. October 3, 2002. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Akira Toriyama Car". Anime News Network. January 31, 2005. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "Toriyama to work on Xbox 360 game". Anime News Network. May 17, 2005. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ Brian Ashcraft (March 27, 2007). "Blue Dragon, Toriyama's Final Anime?". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011.

- ^ "DB's Toriyama, I's Katsura to Team Up on 1-Shot Manga". Anime News Network. February 5, 2008. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "Bokurano's Kitoh to Draw One-Shot Manga in Jump Square". Anime News Network. March 3, 2008. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "Dragon Ball's Toriyama, DNA²'s Katsura to Launch Jiya Manga". Anime News Network. December 1, 2009. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ Schilling, Mark (March 12, 2002). "20th Century Fox to roll with $100m Dragonball". Screen Daily. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ 新作映画「原作者の意地」 鳥山明さん独占インタビュ. Asahi Shimbun (in Japanese). March 30, 2013. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ Ashcraft, Brian (April 2, 2013). "Didn't Like Hollywood's Dragon Ball Movie? Well, Neither Did Dragon Ball's Creator". Kotaku. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ "Dragonball's Toriyama Sketches Ayumi Hamasaki as Goku". Anime News Network. February 3, 2009. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ a b "'Dragon Ball' creator creates manga to raise environmental awareness". Asahi Shimbun. April 13, 2013. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- ^ お待ちかね!鳥山明の新作「KINTOKI」がジャンプに掲載 (in Japanese). Natalie. November 15, 2010. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ^ Warren, Emily (March 16, 2011). "Manga and Anime industries react to earthquake crisis". Asia Pacific Arts. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ "2013 Dragon Ball Z Film's Full Teaser & English Site Posted". Anime News Network. August 7, 2012. Archived from the original on November 18, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "One Piece/Dragon Ball Z Ticket Set Illustrated by Creators". Anime News Network. November 14, 2012. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c "'World of Dragon Ball' Exhibit to Open in Japan in March". Anime News Network. January 21, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ "ANIME NEWS: Latest 'Dragon Ball Z' film nabs 2 million viewers in 23 days". Asahi Shimbun. April 27, 2013. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ "Dragon Ball's Toriyama to Launch Ginga Patrol Jako Manga". Anime News Network. June 26, 2013. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ "Viz's Weekly Shonen Jump Adds New Akira Toriyama Series". Anime News Network. July 1, 2013. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved July 1, 2013.

- ^ Nelkin, Sarah (November 17, 2014). "1st Key Visual For 2015 Dragon Ball Z Film Reveals Frieza". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ "『ドラゴンボール超』11巻発売記念!とよたろう先生直撃インタビュー&仕事場を大公開‼". Dragon Ball Official Site (in Japanese). December 3, 2019. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved January 10, 2020.

- ^ Ressler, Karen (November 7, 2018). "Dragon Ball Super: Broly Film's Final Trailer Streamed". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on January 20, 2019. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ Harrison, Will (July 23, 2021). "Dragon Ball Super: Super Hero character concepts revealed at SDCC 2021". Polygon. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "清須市制20周年ロゴ 漫画家の鳥山明さん考案 代表作はドラゴンボール". Yomiuri Shimbun (in Japanese). January 28, 2024. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Sand Land: The Series Anime Reveals March 20 Premiere, Cast for New Arc". Anime News Network. March 4, 2024. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Dragon Ball Daima Anime Series Reveals Staff". Anime News Network. November 20, 2023. Archived from the original on February 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ 「5億円」プラス「お嫁さん」—「アラレちゃん」鳥山明の結婚式. FOCUS (in Japanese). No. 19. Shinchosha. May 14, 1982. p. 18.

- ^ Toriyama, Akira (2009). Dr. Slump, Volume 18. Viz Media. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4215-2000-1.

- ^ "ドラゴンボール 冒険SPECIAL". Weekly Shōnen Jump (in Japanese). Shueisha. December 1, 1987.

- ^ Toriyama, Akira (2007). Dr. Slump, Volume 13. Viz Media. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4215-1057-6.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama". Weekly Shōnen Jump (in Japanese). No. 20. Shueisha. April 27, 1987.

- ^ Toriyama, Akira (2003). Dragon Ball Z, Volume 8. Viz Media. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-56931-937-6.

- ^ Nightingale, Ed (March 8, 2024). "Tributes shared as Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama passes away". Eurogamer.net. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Kawase, Shinichiro (March 8, 2024). "鳥山明さん死去 「愛知の星です」バード・スタジオ前に訪れたファン". Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Loveridge, Lynzee (May 31, 2019). "Dragonball Creator Akira Toriyama Knighted by France". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ a b Chapman, Paul (December 30, 2016). "Akira Toriyama Dishes on Designing Characters for "Dragon Quest"". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ "Manga wieder ganz groß auf der Buchmesse". Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (in German). March 28, 2004. Archived from the original on July 1, 2004. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ Padula, Derek (January 22, 2016). "Tori-bot's Real Name Discovered". The Dao of Dragon Ball. Archived from the original on January 12, 2024. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ a b c Toriyama, Akira (2008). Dr. Slump, Volume 14. Viz Media. pp. 18, 62, 145. ISBN 978-1-4215-1058-3.

- ^ Toriyama, Akira (2005). Dr. Slump, Volume 2. Viz Media. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-59116-951-2.

- ^ Fan, Wang (March 8, 2024). "Dragon Ball: Japan manga creator Akira Toriyama dies". BBC News. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Speed, Jessica (March 8, 2024). "Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama dies at 68". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Sun, Michael (March 8, 2024). "Akira Toriyama, creator of Dragon Ball manga series, dies aged 68". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "鳥山明さん 命を奪った急性硬膜下血腫とは ほとんどが頭部外傷によるもので死亡率は60%". Sports Nippon (in Japanese). March 8, 2024. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama dies: Dragon Ball fans grieve loss of the anime, manga creator". Hindustan Times. March 8, 2024. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ Walrath-Holdridge, Mary. "Fans, social media pay tribute to 'Dragon Ball' creator Akira Toriyama following death". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "全米SNS上でも鳥山明さん訃報にコメント相次ぐ 一時、Xトレンドランキングで鳥山明さんと「ドラゴンボール」が1位と4位に" (in Japanese). TBS News. March 8, 2024. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 11, 2024.

- ^ Harding, Daryl. "Dragon Ball Creator Akira Toriyama Passes Away at Age 68". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Egan, Toussaint (March 8, 2024). "Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama dies at 68". Polygon. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2024.

- ^ "孫悟空の像と悲しみの記念撮影 外国人観光客も鳥山明さんしのぶ". Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). March 9, 2024. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "【追悼の声】漫画家 鳥山明さん死去 68歳 「DRAGON BALL」など". NHK (in Japanese). March 9, 2024. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Takenaka, Kiyoshi (March 8, 2024). "'Dragon Ball' creator Akira Toriyama dies at 68". Reuters. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Romney, Stephen (March 9, 2024). "Entertainment, world leaders mourn Akira Toriyama". FOX 13 News Utah (KSTU). Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "French leaders pay tribute to 'Dragon Ball' artist on social media". NHK WORLD. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Valentine, Evan (March 8, 2024). "Dragon Ball: China Mourns Akira Toriyama in Official Government Statement". Comicbook.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "El Salvador Lamenta Muerte De Creador De "Dragon Ball", Cómic Favorito De Bukele". Barrons (in Spanish). March 8, 2024. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (March 12, 2024). "IGN: Live-Action Goku Actor Pays Tribute to Akira Toriyama by Apologizing for Dragonball: Evolution". IGN. Archived from the original on March 12, 2024. Retrieved March 23, 2024.

- ^ Tapia Sandoval, Anayeli (March 8, 2024). "Muerte de Akira Toriyama: Mario Castañeda y otros actores de doblaje lamentan deceso del mangaka, creador de Dragon Ball". Infobae (in Spanish). Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama given final goodbye with massive genkidama at Zócalo in Mexico City". SanDiegoRed. March 10, 2024. Archived from the original on March 11, 2024. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "『声優アワード』異例の黙とうで開幕 鳥山明さん・TARAKOさんの訃報受け15秒間". Oricon (in Japanese). March 9, 2024. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Dragon Ball fans in Buenos Aires gather to mourn creator Akira Toriyama, archived from the original on March 11, 2024, retrieved March 11, 2024

- ^ Contreras, Ulises (March 25, 2024). "Dragon Ball: más de 40 artistas peruanos hacen un gran mural en honor a Akira Toriyama". Yahoo! Finance (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ Senzatimore, Renee (March 25, 2024). "Massive Dragon Ball Mural Reveals Over 70 Franchise Characters in Akira Toriyama Tribute". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved March 26, 2024.

- ^ a b DRAGON BALL 大全集 3: TV ANIMATION PART 1 (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. pp. 202–207. ISBN 4-08-782753-4.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama × Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru". TV Anime Guide: Dragon Ball Z Son Goku Densetsu (in Japanese). Shueisha. 2003. ISBN 4088735463.

- ^ The Dragon Ball Z Legend: The Quest Continues. DH Publishing Inc. 2004. p. 7. ISBN 9780972312493.

- ^ "Interview — Dragon Power / Ask Akira Toriyama!". Shonen Jump (in Japanese) (1). January 2003.

- ^ a b "Akira Toriyama Q&A". Training the Manga Mind (in Japanese). Shueisha. March 19, 2010. pp. 37–42.

- ^ a b "Shenlong Times 1". Dragon Ball 大全集 1: Complete Illustrations (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995.

- ^ "Interview de l'éditeur de Dragon Ball - L'influence de Dragon Ball - Partie 6" (in French). Archived from the original on September 28, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2017 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere; Matsuba Ryoko, eds. (2019). "Interview: Torishima Kazuhiko". The Citi Exhibition: Manga. The British Museum. Thames & Hudson. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-500-48049-6.

- ^ Pinon, Matthieu; Lefebvre, Laurent (2023). A History of Modern Manga. Simon and Schuster. p. 83. ISBN 9781647229146.

- ^ Kido, Misaki; Bae, John (2012). "EXCLUSIVE: Masakazu Katsura Spotlight". Viz Media. Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Lauren (November 18, 2014). "The Oral History Of The Poop Emoji (Or, How Google Brought Poop To America)". Fast Company. Archived from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Healy, Claire (May 12, 2015). "What does the stinky poop emoji really mean?". Dazed. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Wiedemann, Julius (September 25, 2004). "Akira Toriyama". In Amano Masanao (ed.). Manga Design. Taschen. p. 372. ISBN 3-8228-2591-3.

- ^ The Dragon Ball Z Legend: The Quest Continues. DH Publishing Inc. 2004. p. 7. ISBN 9780972312493.

- ^ Dragon Ball 大全集 1: Complete Illustrations [Dragon Ball Complete Works 1: Complete Illustrations] (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. pp. 206–207. ISBN 4-08-782754-2.

- ^ Dragon Ball 大全集 4: World Guide [Dragon Ball Complete Works 4: World Guide] (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. pp. 164–169. ISBN 4-08-782754-2.

- ^ "Akira Toriyama". Nintendo Power. Vol. 221. Future US. November 2007. pp. 78–80.

- ^ "Yuji Horii interview". Play. Archived from the original on March 25, 2006. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Maragos, Nich (May 19, 2005). "Previews: Dragon Quest VIII". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ^ DRAGON BALL 大全集 5: TV ANIMATION PART 2 (in Japanese). Shueisha. 1995. pp. 206–210. ISBN 4-08-782755-0.

- ^ "Interview with Yuji Horii". IGN. March 26, 2007. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "Interview with the Majin! Revisited". Shonen Jump. Vol. 5, no. 11. Viz Media. November 2007. p. 388. ISSN 1545-7818.

- ^ Yadao, James S. The Rough Guide to Manga. Penguin Books, October 1, 2009. p. 116 Archived July 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine-117. ISBN 1-4053-8423-9, 9781405384230. Available on Google Books.

- ^ a b Iwamoto, Tetsuo (March 27, 2013). "Dragon Ball artist: 'I just wanted to make boys happy'". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on April 1, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c St. Michel, Patrick (March 15, 2024). "Akira Toriyama's gift to the world". The Japan Times. Retrieved March 16, 2024.

- ^ Brothers, David (September 7, 2011). "Akira Toriyama's 'Dragon Ball' Has Flawless Action That Puts Super-Hero Books to Shame". ComicsAlliance. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016.

- ^ One Piece Color Walk 1. Shueisha. 2001. ISBN 4-08-859217-4.

- ^ Uzumaki: the Art of Naruto. Viz Media. 2007. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-1-4215-1407-9.

- ^ Hodgkins, Crystalyn (November 8, 2011). "Interview: Hiro Mashima". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on February 9, 2013. Retrieved March 24, 2013.

- ^ Morrissy, Kim (February 25, 2019). "Interview: Boruto Manga Artist Mikio Ikemoto". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- ^ Manry, Gia (March 11, 2011). "Seattle's Sakura-Con Hosts Manga Creator Atsushi Suzumi". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Suzuki, Haruhiko, ed. (December 19, 2003). "Dragon Ball Children". Dragon Ball Landmark (in Japanese). Shueisha. pp. 161–182. ISBN 4-08-873478-5.

- ^ "Manga+Comics: A Midnight Opera". Tokyopop. Archived from the original on January 11, 2010. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

Hans' art sensibilities have been strongly influenced by Japanese artists, especially Go Nagai (Devilman) and Akira Toriyama (Dragon Ball).

- ^ Srisirirungsimakul, Nuttaporn (February 13, 2009). "Interview with Wisut Ponnimit for BK". Asia City. Archived from the original on April 23, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ Ohanesian, Liz (November 17, 2014). "Manga Series Dragon Ball Celebrates 30th Anniversary". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ Itier, Emmanuel (December 14, 2021). "Bande-annonce Les Bad Guys : "Du Tarantino pour les enfants !" selon le réalisateur". AlloCiné (in French). Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Loo, Egan (March 4, 2008). "Oricon: Nana's Yazawa, DB's Toriyama are Most Popular". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ 『日本の漫画史を変えた作家』、"漫画の神様"手塚治虫が貫禄の1位. Oricon (in Japanese). July 16, 2010. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ^ Loo, Egan (February 4, 2013). "Akira Toriyama Wins Anniversary Award at France's Angoulême". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ Melrose, Kevin (February 4, 2013). "Robot 6 Willem and Akira Toriyama win top Angoulême honors". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- ^ "ANIME NEWS: 'Dragon Ball' creator Akira Toriyama honored at Angoulême comic festival". Asahi Shimbun. February 13, 2013. Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ^ "POLL: Top Mangaka Who Best Represent Japan". Crunchyroll. February 7, 2014. Archived from the original on May 11, 2021. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- ^ Cano, E. B. (2014). "Ogyges Kaup, a flightless genus of Passalidae (Coleoptera) from Mesoamerica: nine new species, a key to identify species, and a novel character to support its monophyly". Zootaxa. 3889 (4): 471, 480. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3889.4.1. PMID 25544280. Archived from the original on April 23, 2021. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Pinto, Ophelia (May 31, 2019). "Akira Toriyama nommé Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres". HuffPost (in French). Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- ^ "Hall of Fame 2019 Nominees". San Diego Comic-Con. Archived from the original on January 18, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ Pineda, Rafael Antonio (December 14, 2023). "Akira Toriyama, Ryousuke Takahashi, Toshio Furukawa, Yuji Ohno, More Win TAAF's Lifetime Achievement Awards". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 14, 2023. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ "DB's Toriyama, I's Katsura to Team Up on 1-Shot Manga". Anime News Network. February 5, 2008. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ "Bokurano's Kitoh to Draw One-Shot Manga in Jump Square". Anime News Network. March 3, 2008. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

- ^ [鳥山明ほぼ全仕事] 平日更新24時間限定公開!. Dragon Ball Official Site (in Japanese). Shueisha. May 23, 2018. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018.

- ^ [鳥山明ほぼ全仕事] 平日更新24時間限定公開! 2018/11/12. Dragon Ball Official Site (in Japanese). Shueisha. November 12, 2018. Archived from the original on November 12, 2018.

- ^ 広島県にジャンプショップ誕生--鳥山明作"ジャンタ"は広島名物のアレに乗る. Excite.co.jp (in Japanese). January 9, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ [鳥山明ほぼ全仕事] 平日更新24時間限定公開! 2019/03/12. Dragon Ball Official Site (in Japanese). Shueisha. March 12, 2019. Archived from the original on March 12, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ [鳥山明ほぼ全仕事] 平日更新24時間限定公開!. Dragon Ball Official Site (in Japanese). Shueisha. April 19, 2018. Archived from the original on April 19, 2018.

- ^ てんしのトッチオ (in Japanese). Shueisha. Archived from the original on May 24, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- ^ Peters, Megan (May 3, 2018). "'Dragon Ball Z' Reveals Original Logos By Akira Toriyama". ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

Further reading

- Richard, Olivier (2011). Akira Toriyama: le maître du manga (in French). 12 bis. ISBN 978-2-35648-332-4.

External links

- Akira Toriyama at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Akira Toriyama

- 1955 births

- 2024 deaths

- Anime character designers

- Chevaliers of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres

- Grand Prix de la ville d'Angoulême winners

- Japanese cartoonists

- Manga artists from Aichi Prefecture

- Mechanical designers (mecha)

- Mythopoeic writers

- People from Nagoya

- Deaths from subdural hematoma

- Video game artists